Beyond the White Boned Demon

September 5, 2001

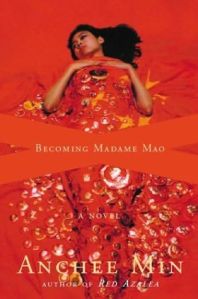

Anchee Min, Becoming Madame Mao, Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 2001

Reviewed by Neralie Hoadley

Ambitious both in its undertaking and its realisation, Becoming Madame Mao is a historical novel about the life of Mao Tse-tung’s last wife. By following Jiang Ching from her birth in 1919 to death in 1991, Min gives the reader a grand sweep through twentieth century Chinese history. She also attempts to explain the apparently inexplicable: Jiang Ching’s role in the tragedy of the Cultural Revolution. This is a fearsome task but Min is not afraid.

Ambitious both in its undertaking and its realisation, Becoming Madame Mao is a historical novel about the life of Mao Tse-tung’s last wife. By following Jiang Ching from her birth in 1919 to death in 1991, Min gives the reader a grand sweep through twentieth century Chinese history. She also attempts to explain the apparently inexplicable: Jiang Ching’s role in the tragedy of the Cultural Revolution. This is a fearsome task but Min is not afraid.

In this book, Min is embarking on new territory as a writer. Min’s remarkable autobiography Red Azalea and her earlier novel Katherine both touch on the Cultural Revolution. They give powerful and disturbing insights into the experience of such social upheaval, but neither tries to make any sense of the events. In fact, in these two books Min is content to let the senselessness of her subject matter speak for itself. She resorts very little to editorialising. In Becoming Madame Mao, however, Min is forced to hypothesise about the motivation of one of the key players in the cataclysm, and thus explain, to some extent, why it erupted. In doing this she never resorts to glib labels of the ‘psychopath’ or ‘megalomaniac’. Rather, she creates a convincing portrait of a strong woman – who considers herself a worthy partner in her husband’s great endeavour – warped by years of frustration and exclusion.

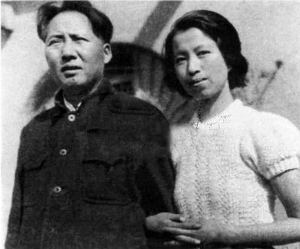

Min does not accept the strangely bifocal vision that has allowed people, both in China and the West, to regard Mao as a creative giant with minor faults while his wife and partner is perceived as an irredeemably destructive upstart. Min depicts the remorseless cruelty of Jiang Ching’s role in the Cultural Revolution as an outgrowth of devotion to her husband and his policies. This understanding is grounded in Min’s belief that the marriage between Mao and Jiang Ching was a love match on both sides. Certainly, Min allows that there were elements of opportunism present both for Mao and for the young actress, Jiang Ching, at the time of their first meeting in 1938. Mao was taking advantage of the absence of his wife – the revolutionary heroine, Zi-zhen, who he had despatched to the Soviet Union – to capitalise on the attentions of a pretty devotee. Jiang Ching, for her part, engineered an introduction to Mao clearly with an eye to where it might lead for her own benefit. Nevertheless, Min paints the development of their relationship as one of love, with a passionate physical connection. This is the lynchpin on which she hangs her understanding of the obsessive behaviour and disregard for common sense that characterised Jiang Ching’s later life. Min convincingly depicts Jiang Ching’s violent extremism as the twisted progeny of a grand passion. In grand passions, obsessions are manifest. They rarely allow room for common sense. It is trite to observe that people find their lives taking strange, sometimes quite crazy, turnings because of the passionate attachments they form, particularly sexual attachments. However, the power ordinary people have to spread their craziness around extends only to those in their own family or immediate vicinity. The power of Mao and Jiang Ching, by contrast, was unspeakably huge.

In all three of her books, Min writes well about female sexual desire, acknowledging its subtleties and ambivalences but never shirking to face its power. This is rare and significant. In Red Azalea Min writes of the desperate and dangerous affair she had with her platoon leader, Yan, and conveys the power this lesbian relationship had both to sustain and imperil her in the harsh years she spent as a conscripted agricultural labourer. In Katherine she explores attraction based on a narcissistic recognition of aspects of the self in the other person. In Becoming Madame Mao, the central relationship is between Jiang Ching and Mao Tse-tung, although Jiang Ching had already been married three times by the time she met Mao in the caves of his Yenan headquarters. The first of these marriages was a forgettable transaction entered into as a way out of financial difficulties, but the next two were complex and rather tortured affairs which certainly crystallised the quality of strength that Jiang Ching was seeking when she set her sights on Mao. Central to Min’s interpretation of this relationship is the driving force in female desire for a sense of on-going connection. From the very early days, she depicts Jiang Ching as aching to have a connection with Mao that is not confined to sex. She pines for acknowledgment of her self and her status in the other areas of Mao’s life. Thus, she is shown as bitterly resentful of the contract she was forced to sign before the Communist Party sanctioned her marriage to Mao, undertaking that she would take no part in his public affairs, nor attempt to influence him in any way. In effect she is instructed to refrain from any type of conversation that ventured out of the purely domestic. Min’s hypothesis is that Jiang Ching’s talents turned sour because of festering frustration. Jiang Ching was strong and able but was excluded from the role in public life that she considered she had earned not only by her marriage, but also through her commitment to the revolutionary cause and the hardships she had endured. Certainly, Jiang Ching left no doubt about whom she blamed for thwarting her. They were top of the list for various forms of persecution when power came into her hands.

There was another important element in Jiang Ching’s rage and bitterness. This was the way that Mao ran hot and cold in his treatment of her. His attentions fluctuated wildly and in ways she could neither predict nor control. Despite her powerlessness, she couldn’t stop trying to attract and sustain his interest. But, by the time they moved to Beijing in 1949, they were living in separate quarters. Thus, the beautiful and luxurious section of the Forbidden City that became her home became also her isolation ward, her prison, tantalisingly close to power but not part of it. From the moment that Mao took up the official reins of power, Jiang Ching was cut off from his public life. She sensed that she was dependant upon Mao’s favour for the few strings she could pull, and was constantly relearning that she had only bare threads still to pull with Mao himself. Jiang Ching was left to brood on her grievances for a couple of decades. However, during this time she gradually asserted her influence in the cultural realm, which was seen by the party as removed enough from real power to be unproblematic. The party was mistaken. Jiang Ching’s cultural activities, such as those associated with the Army’s Socialist Education Campaign and her cultivation of a coterie of musicians and performers, gave her a launching pad. In the aftermath of his appallingly ill-conceived Great Leap Forward, which had led to the death of millions, Mao needed support and turned to his wife. Jiang Ching found that the threads she still held were strong enough to have an effect when she tugged them. In Min’s account, her long-standing association with Kang Sheng, director of Mao’s intelligence service, came into its own at this point. Under Kang’s guidance, she was able to capitalise on Mao’s need of her and dramatically consolidate her own position.

There was another important element in Jiang Ching’s rage and bitterness. This was the way that Mao ran hot and cold in his treatment of her. His attentions fluctuated wildly and in ways she could neither predict nor control. Despite her powerlessness, she couldn’t stop trying to attract and sustain his interest. But, by the time they moved to Beijing in 1949, they were living in separate quarters. Thus, the beautiful and luxurious section of the Forbidden City that became her home became also her isolation ward, her prison, tantalisingly close to power but not part of it. From the moment that Mao took up the official reins of power, Jiang Ching was cut off from his public life. She sensed that she was dependant upon Mao’s favour for the few strings she could pull, and was constantly relearning that she had only bare threads still to pull with Mao himself. Jiang Ching was left to brood on her grievances for a couple of decades. However, during this time she gradually asserted her influence in the cultural realm, which was seen by the party as removed enough from real power to be unproblematic. The party was mistaken. Jiang Ching’s cultural activities, such as those associated with the Army’s Socialist Education Campaign and her cultivation of a coterie of musicians and performers, gave her a launching pad. In the aftermath of his appallingly ill-conceived Great Leap Forward, which had led to the death of millions, Mao needed support and turned to his wife. Jiang Ching found that the threads she still held were strong enough to have an effect when she tugged them. In Min’s account, her long-standing association with Kang Sheng, director of Mao’s intelligence service, came into its own at this point. Under Kang’s guidance, she was able to capitalise on Mao’s need of her and dramatically consolidate her own position.

It is notable that the account of the Cultural Revolution in this book is very much through Jiang Ching’s own eyes. Although the Cultural Revolution is Jiang Ching’s period of ascendancy – and thus is pivotal to the story of her life – Becoming Madame Mao gives less of a taste of its impact than do Min’s previous books. Both Red Azalea and Katherine give strange and diverse insights into the intrusion of a great and repressive madness into the public and private realms of ordinary life. There is little of this in Becoming Madame Mao: just one anecdote about tractors stuck in the mud to illustrate the large scale agricultural failure caused by city kids and intellectuals grasping, and being forced to grasp, the means of production. The reader becomes witness to just one full account of public humiliation; and incarcerations, while mentioned numerously, are generally not depicted in a way that more than hints at their horror. There is little about school closures, forced relocations, or re-education camps, and no real sense of the conditions of localised civil war between various Red Guard factions, which at times amounted to gang warfare involving various sectors of the state, the military and the bureaucracy.

However, what Min does achieve is a sense of the power play, the flux and flow of influence and allegiance, the strategic concerns of Jiang Ching and her cohort. Thus the scene of public humiliation and persecution that is depicted is that of Mao’s second in command, Liu Shao-qi, and his wife Wang Guang-mei. This case was close to Jiang Ching’s heart. For years she had nurtured resentment and suspicion of Liu’s influence with Mao, and envy of Wang’s glamorous public role, which she felt to be rightly her own. Hundreds of thousands of Red Guards gloried in the awful scene of degradation of their erstwhile leaders. Liu’s wife was sentenced to die, his son beaten to death at a rally, his three daughters either imprisoned or exiled. Liu himself was bashed, and shut up alone without food, water or medical help until pneumonia claimed him. Jiang Ching’s enemies were vanquished and the affair is presented as a supremely well orchestrated performance without great emotional impact, both in the account of the narrator and the voice of Jiang Ching herself. Some of the brutality is softened, not, I think, intentionally.

Min’s problem is that her natural style is well suited to the voice of the first person, in which both her other books were written. In Becoming Madame Mao she has ventured to alternate between Jiang Ching’s voice and that of an unspecified narrator. It is easy to see why. This gave her the chance to give the reader insights that Jiang Ching could not reasonably be expected to have into her own character and actions. It also gave Min a mechanism to avoid the situation she encountered in Katherine when she improbably required the heroine to hide in a bed in order to overhear an important conversation. However, the alternating voice, sometimes paragraph by paragraph, has serious drawbacks for Min. My impression is that writing in the first person is what comes naturally to her. Perhaps the narrator’s interruptions and interpolations are an editor’s innovation. Mostly, the change of voice is fluent, even barely noticeable, because there is no change in prose style with change of voice. The style remains Min’s short, choppy sentences, often fragmentary, which race the reader through the story, pausing only briefly for breath or the poetic moment. Occasionally though, the narrator comes through as providing an ominous voice-over of the ‘little-did-she-know’ kind. I am not convinced that the narrator’s voice works. Who is she and why is she speaking? The fact that the style does not change with the voice suggests that perhaps the third person voice is supposed to depict a more reflective persona of Jiang Ching herself, pulling together the fragments of her life in retrospect. If this is intended it doesn’t work. The narrator’s voice tells us things that clearly Jiang Ching could not have ever known or acknowledged. Perhaps it is intended to be Nah, Jiang Ching’s daughter. The prologue shows us a jailed but still defiant Jiang Ching begging Nah to write the story. However, she refuses. Thus, it seems that the third person is providing an omnipotent perspective, which only incidentally speaks in the same prose style as Jiang Ching’s own voice.

In this Min has made a regrettable but understandable decision. It is regrettable because Min has a rare talent for seeing through the eyes of her protagonist. Both in Red Azalea and Katherine she is able to show, in ways that are sometimes shocking and always affecting, the way grit and poetry collide in life. The first person perspective gives her writing a remarkable immediacy and authenticity that is diluted by the mixed approach she has adopted here. The decision is understandable because if she had succeeded in providing a credible explanation of Jiang Ching’s actions from Jiang Ching’s own perspective, Min would doubtless have been risking the accusation that she was acting as an apologist for Jiang Ching. However, I think that Min underrated her own capabilities by making this choice. In Red Azalea, Min is able to show her own part in acts of brutality. She doesn’t apologise. She doesn’t editorialise. She just states. It works, not to justify herself in any sense but to show how it was. Readers are left to draw their own conclusions. This could have worked for Madame Mao too. The actions speak so loudly they could have been allowed to speak for themselves.

To say that Becoming Madame Mao does not have the impact or cohesiveness of crafting achieved in Red Azalea is not harsh criticism. In Becoming Madame Mao Min is attempting a much more complex task. She is trying to offer a truthful historical account of a broad sweep of twentieth century history. Regarding the Cultural Revolution, she aims to tell not just what happened but also make a case as to why it occurred. And she wants to tell an operatic tale of tragedy and heroism in which ideals and love battle with human frailty. In all this she succeeds.

Note: I have used the transcription conventions of names and places used by Anchee Min.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Images: Beijing Shots