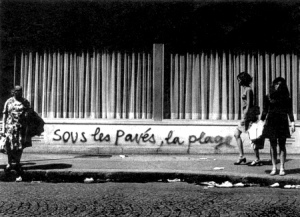

Beneath the paving stones, the beach!

December 16, 2011

McKenzie Wark, The Beach Beneath the Street: The Everyday Life and Glorious Times of the Situationist International, London: Verso, 2011.

Reviewed by Gary Pearce

Last month on some particularly slow news day the Herald Sun rifled the tax-payer-funded reading material of a Greens senator and came up with – quelle horreur! –subversive items such as Slavoj Žižek’s Defence of Lost Causes and McKenzie Wark’s Fifty Years of Recuperation of the Situationist International. On the latter, the Herald Sun explained in its usual unprejudiced way: “Situationist International is an obscure movement of revolutionary Marxists in 1950s France that sought to overthrow capitalism.” That the Situationists should finally make it into the pages of the Murdoch Press is kind of appropriate given how heavily the latter invests in the media homogenisation described in one of that movements key texts, Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle. The Herald Sun has no doubt moved on to fulminate against other targets so its readers might not yet be aware that Wark has now published a new book on the Situationists called The Beach Beneath the Street: The Everyday Life and the Glorious Times of the Situationist International.

I guess one should just be resolved to the idea that the tabloid bafflement and traducements are as reliable indicator as any of things that might be worthy of note and appreciation. The impatience and perplexed responses, if not prejudiced hostility, of the media and local officialdom to the recent occupy movements is a case in point. Indeed, Wark has involved himself with and written about the occupy movement, and like others has noticed how it implies demands outside the conventional modes of political and media discourse and how it suggests new kinds of relationship with the spaces of the city. The novelty of the occupy movement, however, shouldn’t make us overlook some of the important historical resonances contained within it. A case for the ongoing relevance of that “obscure movement” of Situationists can be made here, and, Wark, an ex-pat Australian cultural studies academic, has now written a book that, just at our present conjuncture, commands some attention.

Prior to the global financial crisis, the Arab Spring, the riots in Britain and the occupy movement the Situationists appeared to belong to a time and space far different to our own unquestioned neo-liberal worlds of unversalised economic logic, commodity and spectacle. Wark’s book contains the unstated but detectable presence of German Marxist Walter Benjamin in the way it aims to find an alternative exit from twentieth-century history, and it appears that the Situationists had considerable foresight in seeing where things were headed. As the historical wreckage piles higher, Wark, like Benjamin, wants to look to those historical moments (situations?) when options and hopes still seemed open, and which may still provide the means for moving forward. With their roots in the artistic avant-garde as much as a kind of dissident Marxism, the Situationists were alive to the important problems of individual and society, equality and difference, long since become banal and trivial as evidenced not least in certain media outlets. Part of what has disappeared in our risk-averse times is their ambition to “give form to the world.” Part of what needs to be rethought is the way we go about remembering movements like the Situationists, something that will involve more than “genuflection to dangerous saints” prior to assigning them to the archive and returning to business as usual.

Wark’s intention to brush history against the grain involves seeing the Situationists in all their heterogeneity and complexity rather than, as is more usual, in terms of a homogenous narrative centred on Debord, its most well-known member. Wark reinvests some considerable openness into its historical archive by including those who, although not central figures, came into its orbit and were influenced by and developed its ideas and interests in various ways. The structure and form of the book itself follows from this in its sideways glances, its search for unnoticed resonance and its forging of connections between past and present. The origins of the Situationists are a matter of traces, found in the works of different philosophers, the historical avant garde, the postwar Cobra art movement, but it can be identified most clearly in the Letterist grouping of Ivan Chtchelgov and Isidore Isou. Young Australian artist Vali Myers provides a view of postwar Saint Germaine, the milieu in which Lettrists sought to make space for fresh creation in the ruins. We follow the subsequent formation of the Lettrist International, founded by the young Debord and Gil J. Wolman. We also trace the important background of Danish artist Asger Jorn whose “extreme aesthetics” would play an important role in the eventual formation of Situationist International itself. Along the way we see further articulations of the Situationist project in the novels of Michèle Bernstein and the fleeting presence of Algerian Abdelhafid Khatib. There would be subsequent splits between the Scandanavian and French sections of the Situationists in which different artists/ activists/ theorists/ writers such as Jacqueline de Jong, René Viénet, Alexander Trocchi and Constant Nieuwenhuis would play their various roles.

One of the key Letterist ideas Wark draws attention to is that of “dérive”. He describes this as a “calculated drifting” intent on finding different ways to inhabit or, as we might now say, “occupy” the time and space of the city. This cuts across the structural divisions of work and leisure in particular, in which the latter is usually defined reductively as non-work. “Never work!” insisted Debord. There is here a discernible emphasis on flux, play and adventure, which in the hands of someone like Chtchelgov was pitted against the monumental modernism of Le Corbusier. Wark notes also the breakdown of divisions between subject and exteriority, incorporating a collective experience of the city as “psychogeography”. The Situationists sought their essential viewpoint in those marginal to the city – the “alcoholic intellectuals of the non-working classes”, as Wark calls them –developing a kind of “delinquent critique” situated quite clearly outside the academy. This was a participant/activist “street ethnography” which we might note provides an example for Wark’s approach in this book. There are occasional references in the book to the key figures of French “high theory”, including a nod to Deleuze and Guattari’s “nomadism” in relation to the concept of dérive. For the most part, however, Wark sees high theory as contained by the existing heirarchies of knowledge and art. Rather than develop some remote philosophical originality, Wark is interested in the “low theory” of the Situationists as critical practice and intervention into “everyday life”, the kind of position that is held perhaps by what Wark has described elsewhere as the intellectual as “hacker”.

This leads us to the other important idea of détournement, which Debord and Wolman borrowed from Lautréament. As described by Wark, it refers to the collective appropriation of past and present to be used against contemporary bourgeois worlds. This finds renewed relevance in recent debates on appropriation and piracy in the face of copyright laws intended to protect individual property rights. It’s again an idea that reverberates in the form and structure of Wark’s own book where at one point in the chapter describing détournement he declares: “Needless to say, the best lines in this chapter are plagiarized.” The notion of collective appropriation involves a recognition that culture is held in common and that the role of the subject is up for scrutiny. It is also important as an historical method, aiming to restore subversion to elements that have become institutional and respectable. In the face of Fukuyama’s end of history, it strategises a prising open of history via a negative practice that reveals the gap between everyday life and desires. It also suggests a certain romanticism as a precursor to a more critical modernity. This is part of Jorn’s importance, situated between mysticism and materialism, artistic experiment as much as scientific experiment, subjective truth as well as objective truth. It goes beyond merely aesthetic subjectivity or representation to art as intervening and transforming social practice.

The story of the Situationist International proper begins with its founding in 1957. Members were subject to rigorous strictures and could be excluded, for example, for individual artistic success. Wark quite rightly resists the urge to reduce this to clashing egos, presenting instead a sharpening of focus around what he terms a “provisional micro-society” and its commitment to a new form of collectivity. If the Situationists emerge in part from the artistic world they nevertheless looked to the overcoming of art as a separate practice; art forms just one element of creative practice in the development of new collaborative forms. Nevertheless, there were those with a more artistic focus who constituted the right wing of the movement. There were also those like Constant Nieuwenhuys, known simply as Constant, situated on the left, who looked to the broader project of what he terms the “unitary urbanism of constructed situations”. The Situationists continued to tread the line between romantic revolt and class struggle, with Wark describing Debord’s Society of the Spectacle as a détournement of dissident leftist texts and ideas. This dissidence was present also in Jorn, who criticized socialist as much as bourgeois economics for the abolition of difference and value. They were further influenced by the prominent Marxist Henri Lefebvre and his emphasis on the colonization of “everyday life” through processes of commodification. Lefebvre was important in suggesting that alienation from the real could be negated momentarily in transformative and collective practices cohering into prefigurative “situations” that break through repetition and routine.

The Situationists’ international dimension is evident in the period leading to the London conference in 1960. If Wark highlights new forms of collectivity, he also recognizes the problems that manifest themselves in the exclusions and splits. During this period, the Spur artistic group, which was brought in as the German section of the movement, were distinctive for their essentially Adornonian view of art as a key point of resistance to the rationalization of social life. No sooner had they joined, however, then they ran afoul of the anti-art wing — which included Debord, Attila Kotányi and Raoul Vaneigem — resulting in their rather swift exclusion. Jorn also departed during this period, which meant the loss of someone able to mediate between the theoretical and artistic tendencies within the group. The Scandanavians also left and set up a Second International as a rival and replacement of the Debord group without structures such as the central council, vetting and exclusions. This allowed them subsequently to focus some attention on participatory experiments in art. Another important figure, Jacqueline de Jong, also left and helped set up and edit The Situationist Times. This journal eschewed a consistent line and contained instead resources, concepts and images available for re-use and appropriation.

The story of the Situationists also contained various offshoots and adjacent projects. Alexander Trocchi sought to redefine the “circuits of communication” in his sigma portfolio, described by Wark as “an open-ended series of simple typed and duplicated documents” suggestive of contemporary blogging. As with the Situationists, collaboration and play provided resources for creativity effaced by spectacular society. There is also Constant’s model of New Babylon, which Wark describes as a literalisation of Marx’s model of base and superstructure, with its plans for building spaces that float above ground underpinned by ground-level infrastructure. It sounds slightly mad, but it was more a philosophical project than a realistic model of urban planning. It posited a geography and structure suitable for a set of social relationships beyond the spectacle. In fact, we now have many of the technological transformations imagined by the architecture of the utopian city, but in the absence of social transformation, our current cities are structured around consumerist fantasies underpinned by cheap labour from places like China.

Part of the mysticism surrounding the Situationists stems from its association with the 1960s and with May 1968 in particular. Interestingly, Wark mentions that Debord wrote about the 1965 Watts’ riots which clearly connected to the delinquent and marginalized perspectives of the Situationists. The looting and arson reflected a generalization of the spectacle that made the inequity and general oppression very stark for those in Watts. There have been many riots since, of course, and the most recent in Britain would have occurred after Wark sent his book to press. Situationist accounts tended to exaggerate their own role in the May 68 events and its near overthrow of the French state, but Wark values the view of those like René Viénet as active subjects. Viénet was in all likelihood responsible for the May graffiti, “Beneath the paving stones, the beach!” From the Situationist perspective, the May events were directed against the general degrading of “individuation”, which refers to the authentic sense of self derived from the continuity of collective belonging and connection. If there is a general homogenization of actions and experience at the behest of the commodity, then, to those like Viénet, this moment of barricades, occupation and strikes promised a clearing of ideology and falsification and the possibility of authentic connection and creativity.

Part of the mysticism surrounding the Situationists stems from its association with the 1960s and with May 1968 in particular. Interestingly, Wark mentions that Debord wrote about the 1965 Watts’ riots which clearly connected to the delinquent and marginalized perspectives of the Situationists. The looting and arson reflected a generalization of the spectacle that made the inequity and general oppression very stark for those in Watts. There have been many riots since, of course, and the most recent in Britain would have occurred after Wark sent his book to press. Situationist accounts tended to exaggerate their own role in the May 68 events and its near overthrow of the French state, but Wark values the view of those like René Viénet as active subjects. Viénet was in all likelihood responsible for the May graffiti, “Beneath the paving stones, the beach!” From the Situationist perspective, the May events were directed against the general degrading of “individuation”, which refers to the authentic sense of self derived from the continuity of collective belonging and connection. If there is a general homogenization of actions and experience at the behest of the commodity, then, to those like Viénet, this moment of barricades, occupation and strikes promised a clearing of ideology and falsification and the possibility of authentic connection and creativity.

The legacy of the 60s and the Situationists themselves has long since been incorporated through a haze of nostalgia or via the culture industry. Wark notes also how the disappointments of the 1960s led to the displacement of its energies into high theory, which clearly inform his own field of cultural studies. At this moment when the legitimacy of our current systems and their ideologies are under question, space may well be opening for new détournements of formations and experiences of those like the Situationists. These won’t come in the form of complete and polished narratives, but, like Wark’s, will sift through the shards of theory, tactics, people and works for what may still be useful for critical and radical practices. If Wark is correct here, then, even this late in the day, we might expect new moments of negation, allowing exits from a world that until a brief moment ago had insisted there were none.

I’m an avid reader of Thomas Pynchon, and I just finished watching the film adaptation of Inherent Vice, which prompted me to read the book again. The epigraph for the novel is: “Beneath the paving stones, the beach.” I was just browsing info about the May ’68 events and the paving stones slogan and came upon your review here. It’s very interesting, and a pleasure to read. Thanks.

[…] From a review of The Beach Beneath the Street found at Steep Stairs Review, located here: https://steepstairs.wordpress.com/2011/12/16/beneath-the-paving-stones-the-beach/#comment-1729 […]